Mrs. James Smith and Grandson by Charles Willson Peale, 1776

This painting of a grandmother and grandson was painted at the beginning of the American Revolution. Researcher Laura scrutinized this artwork and made a list of the questions she wanted to investigate.

- Who were Mrs. James Smith and her grandson? Were any members of the Smith family directly involved in the events of the American Revolution?

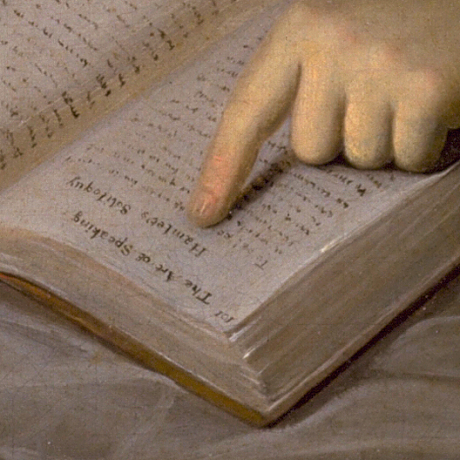

- The grandson points to the famous opening line of Hamlet’s soliloquy, “To be or not to be.” Was the grandson “to be?” Did he reach adulthood and if so, what did he do with his life?

In order to do any research about a portrait it is vital to have the background biographical information about the sitters, especially if you are trying to place them in any historical, political, or social context. One problem with doing research on the life of a woman from the eighteenth- century is that often the title of the portrait only lists her name as Mrs. Somebody, as is the case here. This makes it harder to find out information about her specifically. The inclusion of children in portraits also poses a similar problem, as they are often only referred to as their relation to the adult sitter such as “Daughter” or “Grandson.” These obstacles force you to start your research by looking for information on the closest male relations to the sitters. In this case, it would be the husband of Mrs. Smith and a male member of the generation between the two sitters; Mrs. Smith’s son and the grandson’s father.

My first step was locating a book that contained transcripts of the personal letters of the artist, Charles Willson Peale. When you can, it is always best to search out primary sources first as the information has not been diluted through the years nor has been subject to anyone else’s interpretation. In one of these letters I discovered that Mr. James Smith resided in Donegal Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. I then contacted the Lancaster Historical Society to see if they had any information on him and/ or his wife. They sent me a copy of James Smith’s will, dated 1739, as well as his estate inventory from the same year. In the will it is clearly written that the wife of James Smith was named Mary. It also includes the name of a son, William..But what complicated the research process further for me is the fact that Mary Smith remarried. When Peale painted the portrait she was not Mrs. James Smith, but Mrs. Patrick Campbell. Peale’s diary entries, written when the portrait was painted, record her name as Mrs. Smith (Miller, 1983). The use of the name Mrs. James Smith could either have been an assumption on Peale’s part (as it was William Smith who commissioned the portrait) or, perhaps Peale purposely attached the Smith name to her as this was a generational portrait and either he (or William) wanted to maintain continuity between the two subjects.

The curatorial files on this work of art opened many new doors to possible research for me. These records often contain what a museum already knows about the work and what information has already been published about the work. Through these files I was able to locate a book on Charles Willson Peale’s portraits that gave Mary Smith’s birth year as 1719 and noted her second marriage to Patrick Campbell. Her son William in affection for his step-father, named his own son (the grandson in the portrait) Campbell Smith. Campbell was born in 1768 and went on to serve as a lieutenant and Judge Advocate General in the United States Army from 1792 until 1802 (Sellers, 1952).

I found that it was William Smith who was the most prominent member of the Smith family, having served as a member of the Continental Congress in 1777 and having been elected to the First Congress in 1789. As he served in a public office and was so visible, it was easy to search for information relating to William. I hoped that by tracking down information on William I could fill in the gaps of what I did not know about Mary Smith and Campbell. William was not the only family member to be involved in a public life. By exploring a few biographies on William, I soon learned that his son-in-law Otho Holland Williams was a prominent Continental Army officer. Knowing this allowed me to establish that many of Otho’s papers had been preserved at the Maryland Historical Society. In these papers I found various letters between Otho and his father-in-law William Smith, many of which contained references to Campbell. These letters gave me a better understanding of what Campbell’s life was like after Peale painted his portrait.

In one letter, Otho writes to a Dr. Philip Thomas in 1788 that Campbell was educated in Philadelphia and had been studying law for two years. He had made some progress, yet he was “indiscreet and lured off by false pleasures.” It seems that Campbell’s less-than-perfect behavior did not improve with time. By the following year in 1789 his father William wrote to Campbell’s brother-in-law Otho on August 5th, revealing that Campbell’s behavior had greatly distressed him. He had once thought Campbell promising but feared that that hope was nearly gone. “I . . . once had a son, much loved, But alas he is no more” (Otho Holland Williams Papers, 1789).

I knew Campbell was active in the military from an earlier source (Sellers, 1952) so I searched the online archive, Papers of the War Department, 1784-1800 looking for any primary documentation that could shed more light on Campbell’s life. I found many letters referencing Campbell, as well as some written in his own hand. However, some of the more interesting ones were about Campbell. Apparently his stint in the military had not matured Campbell; if anything his behavior seemed to have become more rebellious and unruly. I found a letter dated July 19, 1798 from a Thomas Lewis to James McHenry. Lewis writes that he is reporting Campbell, aged thirty, for “villainous conduct and mutinous disposition” for declaring the Secretary of War and other officers of state to be a “set of damned eternal rascals” in his presence (Lewis, 1798). You could say that Peale foreshadowed this behavior in the portrait by capturing a slightly impish quality in Campbell’s countenance.

The records and information available for Campbell Smith seem to taper off around 1802; the lack of further information has been interpreted to mean that he died at a relatively young age, probably by 1804. It would be beneficial to our understanding of the portrait to deduce how Campbell died, as this was not made apparent in any of the sources I located.

source: Smithsonian American Art Museum