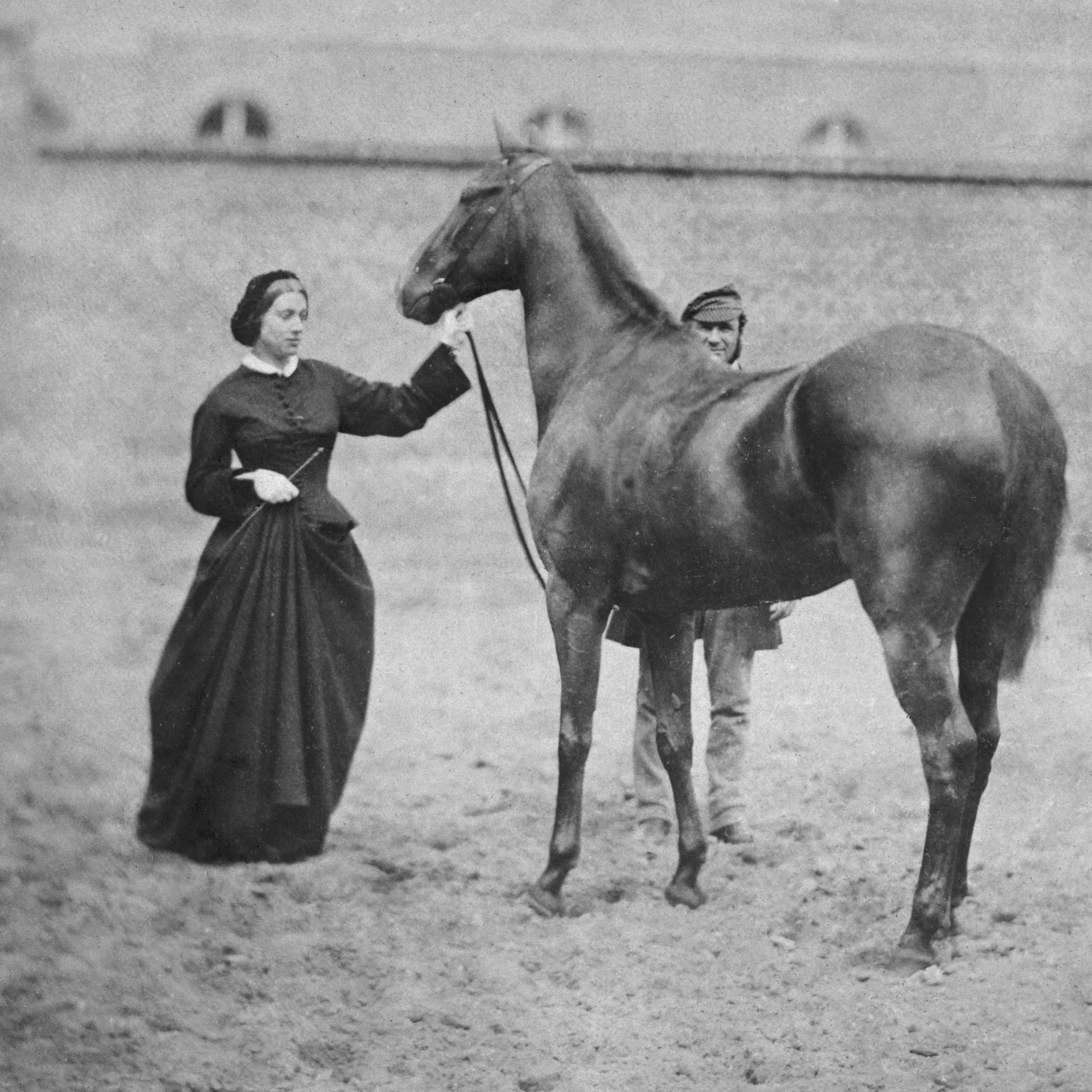

Alexandrine Tinne on horseback by Maurits Verveer, 1860-61

On the back of the photo the following tragic note: “Alexandrine Tinne some time before her depart from the Netherlands. Later, assassinated by indigenous in Africa.” The photo is probably taken in the summer of 1860. She is pictured in the Stables of the Hague, Kazernestraat 50. On my other blogpost here you can see a painting of Tinne, also on horseback, several years earlier.

Read her tragic story (via Wikipedia):

Alexandrine Petronella Francina Tinne (alternative spellings: Pieternella, Françoise, Tinné) (17 October 1835 – 1 August 1869) was a Dutch explorer in Africa and the first European woman to attempt to cross the Sahara. She often went by the first name Alexine.

Alexandrine was the daughter of Philip Frederik Tinne and Baroness Henriette van Capellen. Philip Tinne was a Dutch merchant who settled in England during the Napoleonic wars and later returned to his native land. Henriette van Capellen, daughter of a famous Dutch Vice-Admiral, Theodorus Frederik van Capellen, was Philip’s second wife, and Alexandrine was born when he was sixty-three. Young Alexandrine was tutored at home, and showed a proficiency at piano. Her wealthy father died when she was ten years old, leaving her the richest heiress in the Netherlands.

For the first extensive journey in Central Africa Alexine Tinne left Europe in the summer of 1861 for the White Nile regions. Accompanied by her mother and her aunt, she set out on 9 January 1862. After a short stay at Khartoum the party ascended the White Nile to Gondokoro, the first European women to arrive there. Alexandrine fell ill and they were forced to return reaching Khartoum on 20 November. Directly after their return Theodor von Heuglin and Hermann Steudner met with the Tinne’s and the four of them planned to travel to the Bahr-el-Ghazal, a tributary of the White Nile, in order to reach the countries of the ‘Niam-Niam'(Azande). Heuglin and Steudner left Khartoum on 25 January, ahead of the expedition. The Tinnes followed on 5 February. Heuglin also had a geographical exploration in mind, intending to explore the uncharted region beyond the river and to ascertain how far westward the Nile basin extended; also to investigate the reports of a vast lake in Central Africa eastwards of those already known, most likely the lake-like expanses of the middle Congo.

Ascending the Bahr-el-Ghazal, the limit of navigation was reached on 10 March. From Meshra-er-Rek a journey was made overland, across the Bahr Jur and south-west by the Bahr Kosango, to Jebel Kosango, on the borders of the Niam-Niam country. During the journey all the travelers suffered severely from fever. Steudner died in April and Alexandrine’s mother in July, followed by two Dutch maids. After many fatigues and dangers the remainder of the party reached Khartoum at the end of March 1864, when Miss Tinne’s aunt, who had stayed in Khartoum, died. Alexine Tinne buried her aunt and one maid, and brought the corpse of her mother and the other maid back to Cairo. John Tinne, her half-brother from Liverpool, visited Alexine in January/February 1865, with the intention of talking her into joining him back home. Alexine was not to be persuaded, and John left with the two corpses and a large part of her ethnographic collection. Her mother’s corpse later was buried at the Oud Eik en Duinen cemetery in The Hague. Alexine’s ethnographic collection was donated by John to the Public Museum (now the Liverpool World Museum).

The geographical and scientific results of the expedition were highly important, as will be seen in Heuglin’s Die Tinnésche Expedition im westlichen Nilgebiet (1863–1864 (Gotha, 1865), and Reise in das Gebiet des Weissen Nils Leipzig, 1869). A description, by T Kotschy and J Peyritsch, of some of the plants discovered by the expedition was published at Vienna in 1867 under the title of Plantae Tinneanae, and introduced 24 new species to science, including 19 species in the mint family.

At Cairo Miss Tinne lived in Oriental style during the next four years, visiting Algeria, Tunisia and other parts of the Mediterranean. An attempt to reach the Touaregs in 1868 from Algiers failed.

In January 1869 she again made an attempt to reach the Touaregs. She started from Tripoli with a caravan, intending to proceed to Lake Chad, and thence by Wadai, Darfur and Kordofan to the upper Nile. In Murzuq she met the German explorer Gustav Nachtigal, with whom she intended to cross the desert. As Nachtigal wanted to go to the Tibesti Mountains first, she set out for the South on her own. Her caravan advanced slowly. Due to her diseases (attacks of gout, inflammation of her eyes) she was not able to maintain order in her group.

In the early morning of 1 August on the route from Murzuk to Ghat she was murdered together with two Dutch sailors in her party, allegedly by Tuareg people in league with her escort. According to the statements at the trial in Tripoli in December 1869/January 1870, two blows of a sword (one in her neck, one on one of her hands) made her collapse. They left her to bleed to death. Her body was never found.

There are several theories as to the motive, none of them proven. One is that her guides believed that her iron water tanks were filled with gold. It is also possible that her death came as a result of an internal political conflict between local Tuareg chiefs. Another explorer, Erwin von Bary, who visited the same area in the 1870s, met participants of the assault and learned that it had been a blow against the “great old man” of the Northern Tuaregs, Ikhenukhen, who was to be removed from his powerful position, and the means was to be the killing of the Christians—just to prove that Ikhenukhen was too weak to protect travelers. Given the internal strife among the Northern Tuareg that lasted until the Ottoman occupation of the Fezzan Province (Southern Libya) this version is the most probable explanation of the otherwise unmotivated massacre.

It was believed her collections of ethnographic specimens in the museum at Liverpool, England were destroyed in 1941 during a bombing raid. The church built in her memory in The Hague was similarly destroyed. Recent research revealed however that around 75% (over 100 objects) of her ethnographic collection survived the air raid. Besides their value as an irreplaceable document of her two Sudan journeys in 1862-1864, her collection, together with the contemporary one of Heuglin at Stuttgart (the Linden Museum), represent rare specimens of an early date belonging to material cultures in the Sudan. A small marker near Juba in Sudan commemorating the great Nile explorers of the 19th century bears her name, as well as a window plaque in Tangiers. Many of her remaining papers, including most of her letters from Africa, are stored at the National Archive in The Hague. Her photographs are at the National Archive and the Haags Gemeentearchief (Municipal Archive of The Hague).

Alternate spellings: Alexine Tinne, Alexandrine Tinné.

Further reading

- ‘The Fateful Journey’. The Expedition of Alexine Tinne and Theodor von Heuglin in Sudan (1863-1864). A Study of their travel accounts and ethnographic collections, Robert Joost Willink (Amsterdam, 2011) ISBN 978-90-8964-352-0

- Geographical Notes of an Expedition in Central Africa by three Dutch Ladies, John A Tinné (Liverpool, 1864)

- Travels of Alexine, Penelope Gladstone (London, 1970)

- Tochter des Sultans, Die Reisen der Alexandrine Tinne (in German only), Wilfried Westphal (Stuttgart, 2002)

- The Nile Quest, ch. xvi. Sir HH Johnston, (London, 1903).

- Die Tuareg. Herren der Sahara. Ausstellung der Heinrich-Barth-Gesellschaft (in German only), Cornelius Trebbin & Peter Kremer (Düsseldorf 1986)

- Alexandrine Tinne (1835-1869) – Afrikareisende des 19. Jahrhunderts. Zur Geschichte des Reisens, Antje Köhlerschmidt (Magdeburg 1994; Ph. D. thesis.) – Hitherto the only serious and scholarly account of Alexine’s travels and achievements in the context of 19th-century African exploration.

- McLoone, Margo, Women explorers in Africa: Christina Dodwell, Delia Akeley, Mary Kingsley, Florence von Sass Baker, and Alexandrine Tinne (Capstone Press, 1997)

External links

source: Rijksuseum, Wikipedia, WikiCommons, Nationaal Archief