Georgiana Houghton, ca. 1850s

Georgiana Houghton (1814–1884) was a British artist and spiritualist medium.

Georgiana Houghton was born on April 20th 1814 in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria. She was the seventh of twelve children of Mary Warrand and George Houghton who was a merchant in foreign parts. The family lived in London and spent periods of time overseas in the Canary Islands and Madeira.

She began producing ‘spirit’ drawings in 1859 at private séances. She produced her watercolour drawings to the public at an exhibition at the New British Gallery in Bond Street, London in 1871.

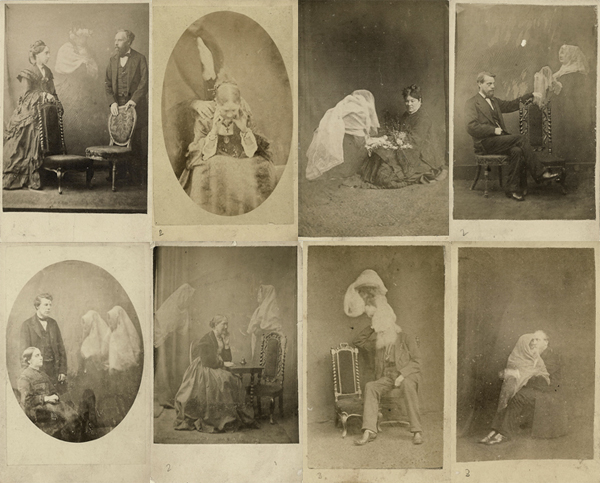

Houghton became associated with the fraudulent spirit photographer Frederick Hudson to sell reproductions of his photographs.

In 1882, Houghton published Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings and Phenomena Invisible to the Material Eye. The book included alleged spirit photographs (for more about the subject see the following link here) from Hudson and other photographers featuring mediums such as Agnes Guppy-Volckman, Stainton Moses and spiritualists Alfred Russel Wallace and William Howitt. The photographs in the book were criticized by magic historian Albert A. Hopkins. He noted how the photographs looked dubious and could easily be produced by fraudulent methods.

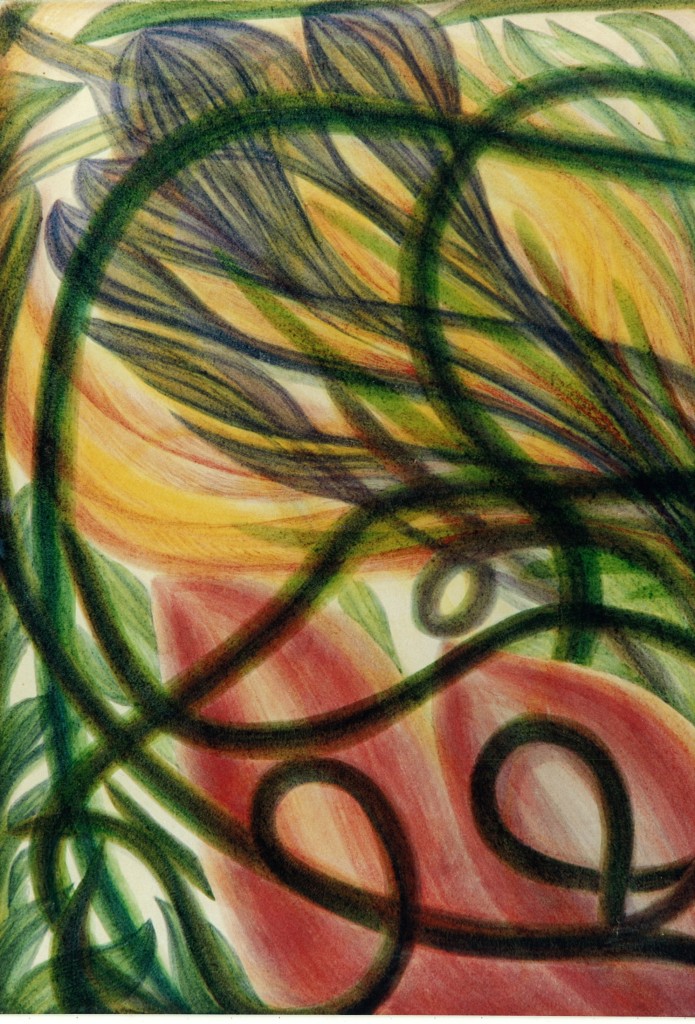

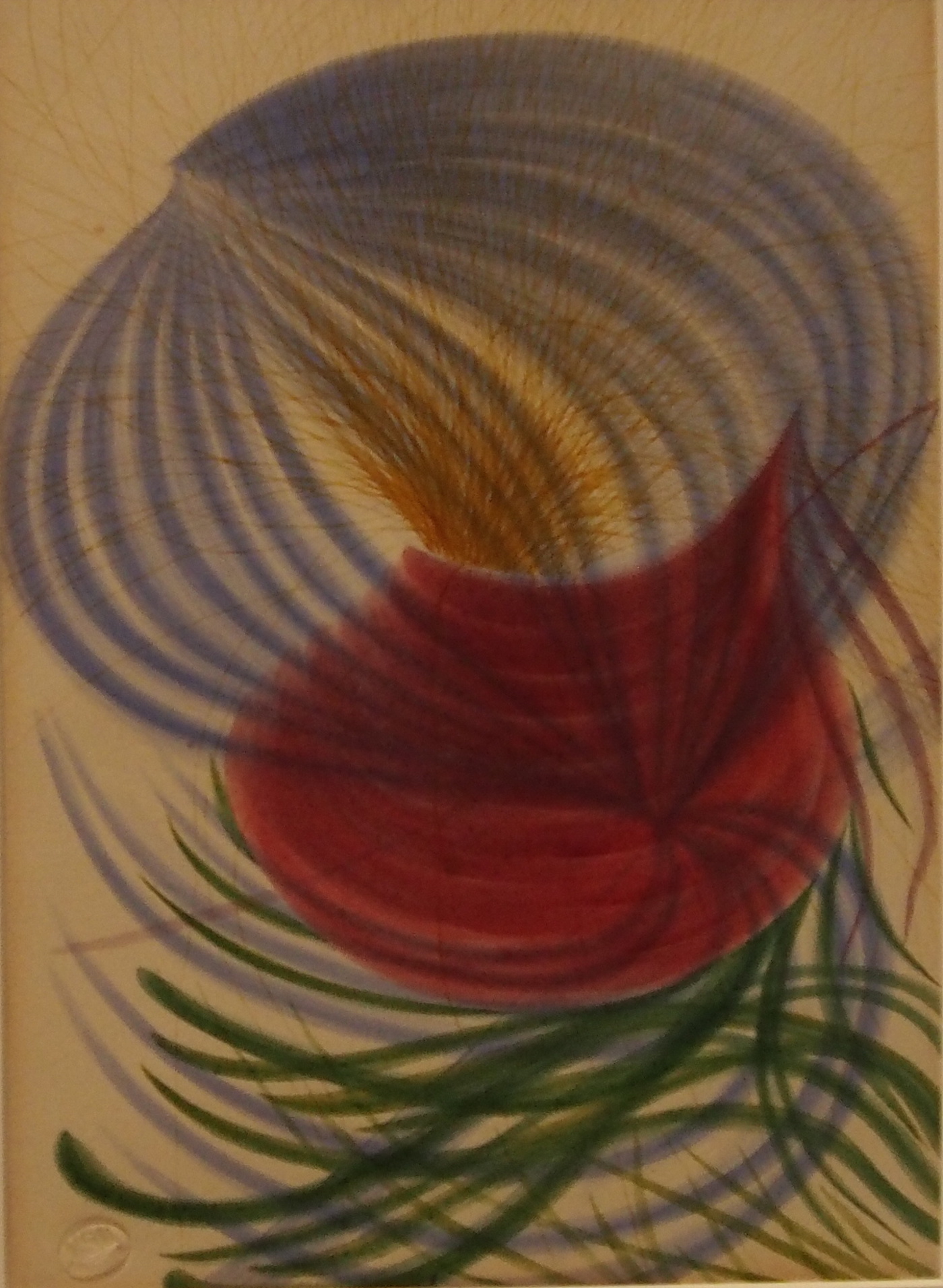

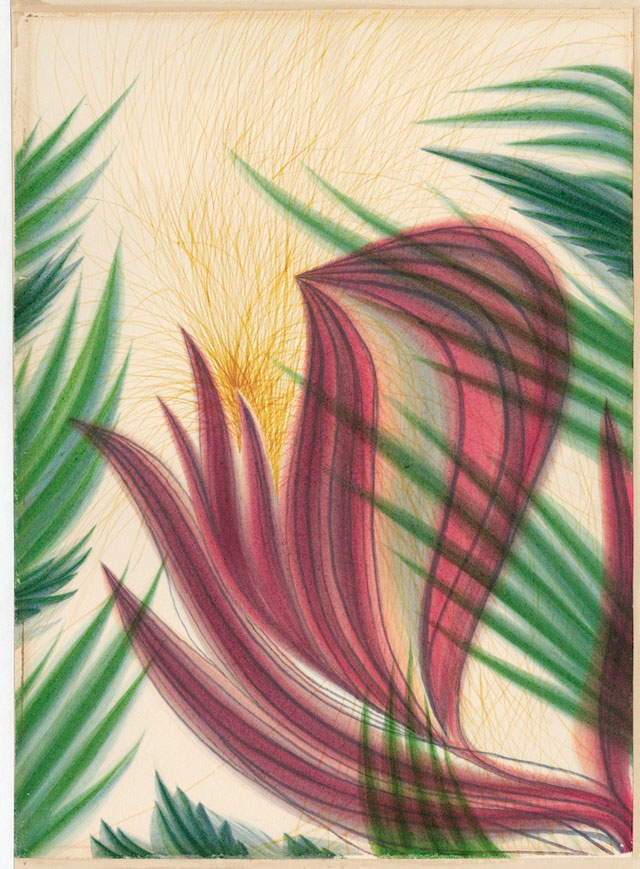

Georgiana Houghton, selections from the Invisible Beings series, 1872-76

Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884) developed skills as a medium after attending her first séance in 1859 and achieved her first spirit drawing in 1861. For the next decade, under the guidance of a spirit called Henry Lenny and 70 Archangels, she produced 155 extraordinary water colour drawings.

Georgiana began each piece without preconception of the outcome. She filled each sheet of paper with woven swirls of vibrant colours forming an intricate layering of hues and tints. Amongst her circle of friends and fellow Spiritualists she soon became recognised as a pioneer of spirit art.

To reach a wider audience and hopefully inspire others to become Spiritualists and develop their own gift as spirit artists, Georgiana single-handedly mounted a solo exhibition which took place from May-September in 1871 at the New British Gallery in Old Bond Street, London.

The exhibition attracted many visitors, some of whom were shocked by the previously unseen abstract forms. Although the show was applauded by several traditional artists, it generally received mixed reviews. By the end of the exhibition only one sale had been made, possibly because the work was seen as too modern for the tastes of Victorian England, or perhaps due to the exorbitant prices placed on the pieces by Georgiana. Either way the end result was that the show was a financial disaster for the artist.

Given that Georgiana appears to have anticipated the abstract art of artists such as Kandinsky by half a century it is surprising that she has been largely ignored by art historians for over a century. However this is slowly changing and with the current re-evaluation by scholars and curators it looks likely that she will soon be recognised as not only a pioneer of spirit art, but modern art as well.

Spiritual Crown of Mrs A A Watts, 1867

In June 2016 a solo exhibition entitled “Spirit Drawings” was organised by the Courtauld Institute of Art, featuring a number of Houghton’s surviving artworks.

Georgiana Houghton was a spiritualist medium who was trained in classical art but gave up painting after the death of her younger sister in 1851. A decade later, after she had become aquatinted with spiritualism she began once more to put coloured pencils and watercolours to paper. However, this time she said it was spirits of the dead who were guiding her hand. Through her mediumship she was acquainted with several Renaissance artists, as well as higher angelic beings. Houghton became the vessel through which they could exorcise their otherworldly aesthetic desires.

The nineteenth century with its ghosts and clairvoyants was the golden age of communion with the spirit world. The afterlife was figured not just as a sacred waiting-room but a place in which spirits continued to ‘live out’ their afterlife – evolving and communicating as they did when they were living. There was a seance in nearly every drawing room, including at Buckingham Palace. The spirits were believed to possess knowledge about moral and ethical issues that transcended our own. – This belief is almost palpable from the mesmeric, twisting force behind Houghton’s brush – her visual language is one of prepossessing immediacy.

Flower of Catherine Emily Stringer by Georgiana Houghton, 1866

In 1871 Houghton rented a gallery in Bond Street and presented 155 of these works to a bewildered London audience. Houghton funded the project with her own money and for two months met visitors in the gallery to speak with them about her work. However, only one painting sold and now only 50 or so remain in known existence.

Flower and Fruit of Henry Lenny, August 28th 1861

The critic from The Era newspaper pronounced it to be ‘the most astonishing exhibition in London at the present moment.’ The Daily News likened the works to ‘tangled threads of colored wool’ and concluded that ‘they deserve to be seen as the most extraordinary and instructive example of artistic aberration.’

Georgiana Houghton, “Flower of Warrand Houghton”, September 18, 1861

.

John Ptak acquired one Houghton’s gallery catalogues from an 1871 art show in London. In her annotations, Houghton explains her unconventional aesthetic process – “In the execution of the Drawings my hand has been entirely guided by Spirits, no idea being formed in my own mind as to what was going to be produced.”

.

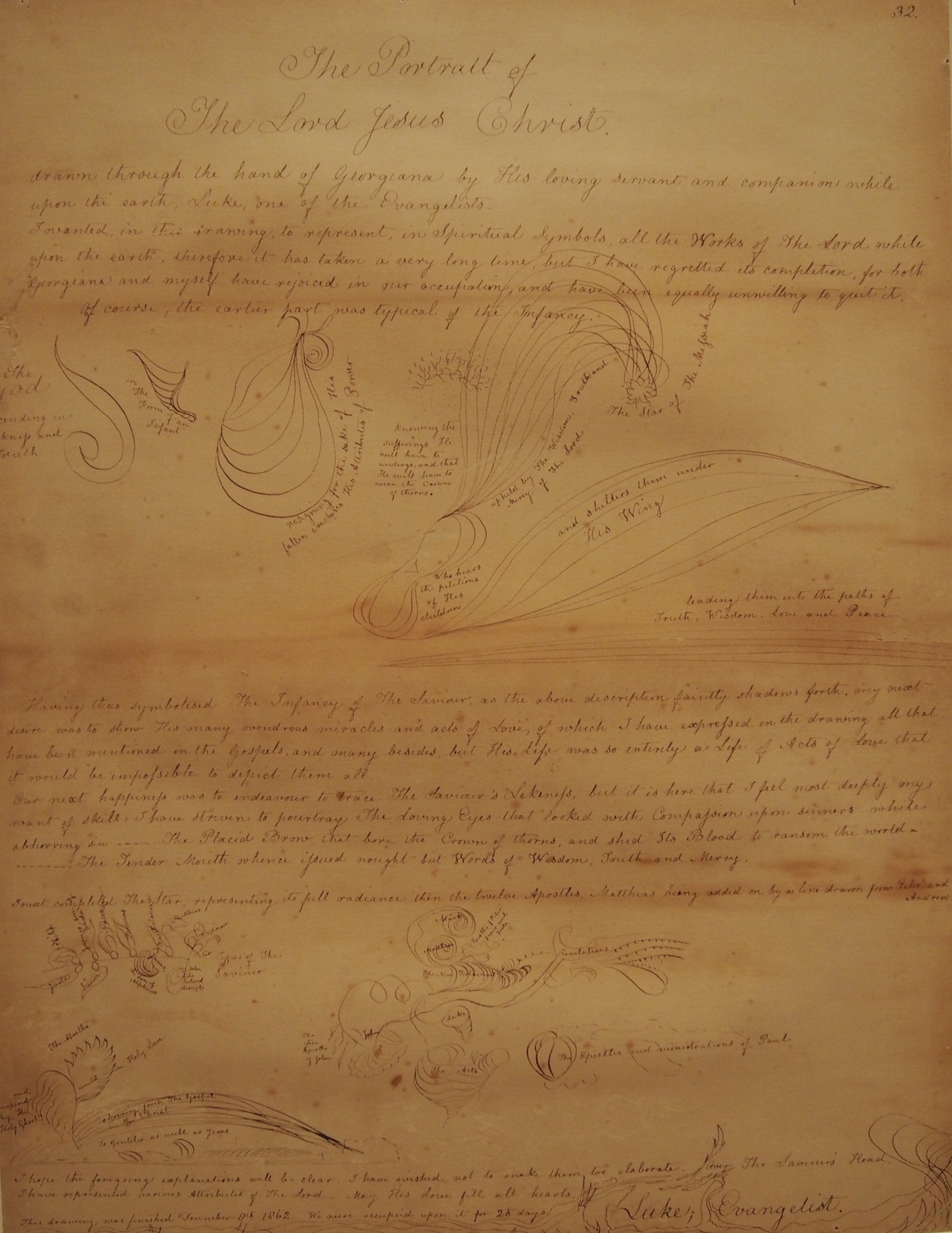

Georgiana Houghton, The Portrait of the Lord Jesus Christ, 1862

Georgiana Houghton, “The Portrait of the Lord Jesus Christ (reverse)” (December 8, 1862)

Houghton set out to ‘obtain mediumship’ by holding hands with her mother at a small table for some months on end waiting for contact — Sundays, she believed, worked best, ‘as we should then be less disturbed by evil influences’.

Georgiana Houghton, ca. 1882

Georgiana was the daughter of Mary Ann Warrand and George Houghton. Sister of Marianne, Roberto, Warrand, George Clarence, Cecil Angelo, Charles James, Sidney Alexander and Helen.

Born in 1814 in Canaries, Georgiana died in 1884, aged 69. She was said to be a famous spiritualist and lived with her parents throughout her life. She wrote a number of books on spiritualism, including

- Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings and Phenomena Invisible to the Material Eye Interblended with Personal Narrative

- Evenings At Home In Spiritual Seance: Welded Together By A Species Of Autobiography

She left a moving account of her father’s accident in April 1863 and of his death six months later in “Spiritual Séance”. It is quite clear not only how fond she was of her father but also her own involement in spiritualism.

In the same book she relates how, after her father’s death, she and her mother decided to move to a smaller house from 5, Upper Craven Place, Highgate road, where the family had lived since 1830. Initially they hoped for compensation as a railway planned to come through the house would have involved its demolition. In the event the railway did not touch either the house or garden but nevertheless came sufficiently close to be a decided nuisance. Her brother Clarence generously agreed to pay the landlord £100 to cancel the lease.

In 1871 Houghton rented a prestigious gallery space in Bond Street and presented 55 of her spirit drawings to a perplexed London audience. The critic from The Era newspaper pronounced it to be “the most astonishing exhibition in London at the present moment.” The Daily News likened the works to “tangled threads of colored wool” and concluded that “they deserve to be seen as the most extraordinary and instructive example of artistic aberration.”

Georgiana Houghton: Spirit Drawings will present more than 20 of these remarkable works. Unlike anything typically associated with Victorian culture, it will be a fascinating opportunity to consider their place within the history of art; both as products of their times and as precursors of radical 20th Century art.

A detail from Glory Be to God by Georgiana Houghton

She has been dismissed as an eccentric, amateur artist who claimed to talk to the dead and receive their help with her watercolours. But Georgiana Houghton’s abstract style is beginning to be recognised as being decades ahead of painters in a similar vein such as Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. Now the fascinating story of the overlooked Victorian artist is to be told in the first UK exhibition of Houghton’s work in nearly 150 years.

It will be presented next month at the Courthauld Gallery in London. The gallery’s curator of 20th-century art, Barnaby Wright, said Houghton’s works were extraordinary and pre-dated works by artists considered abstract pioneers by some 40 years. They are also ahead of works by the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint whose turn-of-the-century abstract works are on display at the Serpentine Gallery in London.

“I think Houghton does count as being among the first abstract artists,” said Wright. “She is obviously earlier than Klint. If one is playing that race then she she steals a march.”

Wright recalled being given an image of a Houghton work. “I fell straight into the trap of saying it was a piece of 1960s or 1970s psychedelia,” he said. “Turns out it was 1865. I was a hundred years out.”

Most of the loans for the Courtauld show are coming from the Victorian Spiritualists’ Union in Melbourne, Australia, the proud owner since 1910 of around 35 works by Houghton.

“In terms of artistic quality they are well above and beyond what one might normally associate with amateur practitioners of an eccentric kind,” said Wright. “These are exquisite as watercolours … they are compelling just on their own terms.”

Georgiana Houghton, “The Risen Lord” (June 29, 1864)

Houghton, born in 1814, was an ardent and well-known promoter of spiritualism, a movement that attracted many believers in Victorian England and was later championed by such figures as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

She was a trained artist and medium and pioneered the use of drawing as a method of channeling and expressing communications with the dead.

Houghton would host a seance, talk to her spirit guide and draw complex, colourful and layered watercolours. They anticipate the works both of abstract 20th-century artists and the later Surrealists who engaged with automatic and unconscious drawings.

Kandinsky and Mondrian were fascinated by spiritualism, although whether they were directly influenced by her work is not known, said Wright.

Houghton initially said she used dead members of her family as spirit guides, such as her late sister Zilla, but later communed with the Renaissance artists Titian and Correggio.

On the back of the works Houghton would, in a form of automatic writing, talk about what particular dots or swirls or colours might have meant.

In 1871 Houghton hired a prestigious gallery space in Bond Street to exhibit 155 of her spirit drawings, spending every day there over the course of three months so she could discuss them with visitors.

Audiences were understandably perplexed by the unfamiliar style, though not necessarily in a bad way. One critic compared the drawings to late Turner. A writer from the Era newspaper called it “the most astonishing exhibition in London at the present moment”.

Another from the Daily News said they were like “tangled threads of cotton wool” and concluded: “They deserve to be seen as the most extraordinary and instructive example of artistic aberration.”

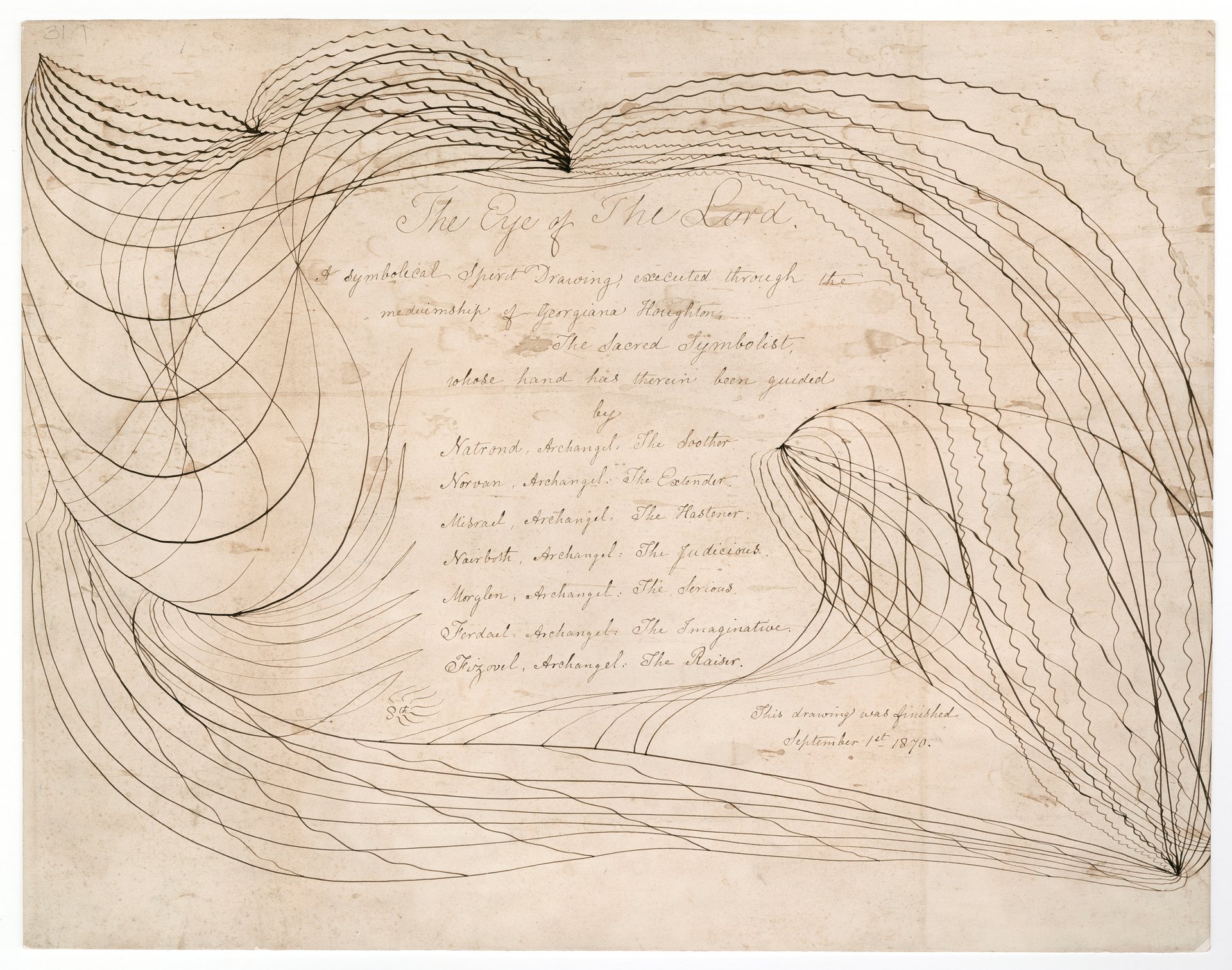

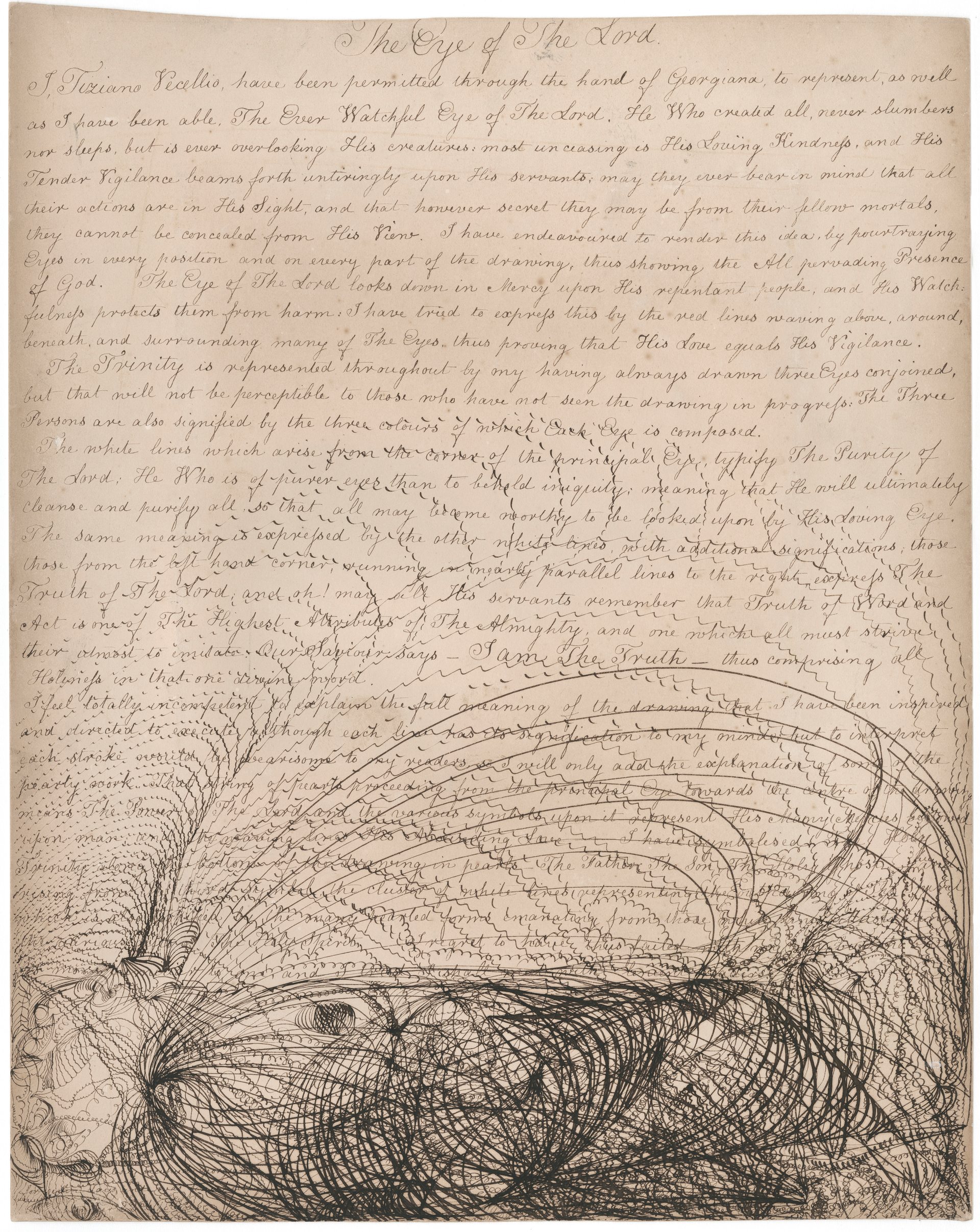

The Eye of the Lord by Georgiana Houghton

The reverse side of The Eye of the Lord

But despite the critical interest, the exhibition was not a commercial success and it almost bankrupted Houghton.

She continued talking to her guides, making her extraordinary near-abstract watercolours, until she joined her friends in 1884.

Wright said Houghton’s watercolours were too good to be dismissed. “They are really captivating and deserve to be thought about rather deeply. They do move you on an emotional level.

“Part of the point of doing the exhibition is to share these works, allow people to engage with them and decide for themselves what power they have as artworks. I certainly believe they have a remarkable visual power and high artistic quality … they deserve to be appreciated and further explored.”

More than 20 are due to go on display at the Courtauld, the first time they will have been seen in a UK show since 1871.

About 50 Houghton works are known about, most of them in Melbourne. The College of Psychic Studies in west London is lending an album of eight works to the exhibition.

Where are the rest? “Somewhere out there is presumably a pretty big cache of these remarkable drawings and we hope one or two might resurface during the show,” said Wright.

Georgiana Houghton, The Sheltering Wing of the Most High, c. 1861-61

It is London in the summer of 1871. Queen Victoria has just opened the Royal Albert Hall in memory of her beloved husband; Lewis Carroll’s sequel to Alice in Wonderland has just been published, and French refugees from the Franco-Prussian war continue to arrive in the capital. Among them is Claude Monet, who is having a miserable time in the fog and mist. Not far from the Thames views that he had been painting, a fellow artist has just opened her first exhibition of 155 ‘Spirit Drawings’ in a gallery on Old Bond Street, in the heart of London’s art quarter.

She was Georgiana Houghton (1814–1884), a 57-year-old London-based middle-class artist and celebrated spiritualist who had for the previous ten years been feverishly working behind closed doors on a series of abstract coloured drawings, which had been produced ‘guided’ by the hand of spirits. Now, with the encouragement of both an artist friend and her ‘invisible friends’, she felt ready to show her extraordinary endeavours to the world.

What she put on display was unlike anything any western artist had made, or any member of the British public had ever seen. The watercolour drawings, a little larger than A4, were intricately detailed abstract compositions filled with sinuous spirals, frenetic dots and sweeping lines. Yellows, greens, blues and reds battled with each other for space on the paper. The densely layered images appeared to have no form, and no beginning or end. There was no traditional perspective to enjoy. There was no mythological subject to interpret; no moral narrative to read, and no hint of portraiture or landscape to scrutinise. Instead, each work was accompanied by a detailed text written in her spidery writing outlining its spiritualist meaning. The drawings were titled accordingly with names such as ‘The Eye of God’ and ‘The Hand of the Lord and Heavenly Hopes’.

Houghton had been formally trained as an artist, possibly in France though we can’t be sure. She had been keen to be seen as such, and in census records she describes herself as ‘artist’. She had submitted her pictures to various prominent art institutions, such as the Royal Academy and the Dudley Museum and Art Gallery (her work was initially accepted by the former), but no one was prepared to take her on, and so her exhibition became the perfect amalgamation of her artistic passion and her religious aims.

But what had Houghton created? It is hard to imagine how radical and bizarre her artworks must have appeared to a Victorian visitor. Here was abstraction more than 35 years before Houghton’s fellow spiritualist and artist Hilma af Klint produced her extraordinary works (recently on show at the Serpentine Gallery). At the time, the average gallery-goer was more likely to see paintings by the Pre-Raphaelites, and the most radical art being painted in London was work like Whistler’s ‘Nocturne: Blue and Silver — Chelsea’ or Monet’s ‘The Thames below Westminster’. So it is no surprise that the critics who reviewed her exhibition wrote with a heady mixture of scorn, hilarity and bafflement.

In one article the reviewer stated that if ‘readers were to imagine such a thing as an accurate copy of coloured and white “Berlin” wools [colourful embroidery works used for house decoration], all tangled together in a flattened mass, framed and hung round a gallery, some idea could be formed of the appearance of this most strange exhibition’. In another, the critic wrote how ‘a visitor to the exhibition is alternatively occupied by sad and ludicrous images during the whole of his stay in this gallery of painful absurdities’, while a third wrote of ‘the strange hallucinations of which the human mind may be capable… If we were to sum up the characteristics of the exhibition in a single phrase, we should pronounce it symbolism gone mad.’

The reality was that nobody had a language to explain these odd-seeming images. While they did suggest forms, these were abstract in nature. As a result, Houghton felt that her art ‘could not be criticised according to any of the known and accepted canons of art’. She was right. How could anyone understand what she was doing? It had never been done before. The term ‘abstract’ was not applied to the visual arts until the 20th century. And while Houghton’s artist contemporaries such as Rossetti, Whistler and Holman Hunt had experienced, to varying degrees, the world of séances and table-tipping, had seen spirit drawing, and were open to the ideas of spiritualism, they didn’t stray from their figurative, allegorical, personal and highly emotionally charged paintings. They were more interested in telling stories through their works, while Houghton’s primary quest was to promote the spiritualist cause and to, as she put it, ‘show what the Lord hath done for my soul’.

Like many Victorians, Houghton had arrived at spiritualism through personal loss — in her case the death of her younger sister, herself an artist. As a method of contacting her in the afterlife, Houghton had rapidly trained as a spirit medium, and soon combined her new-found skill with the practice of drawing that was intended as an illustration of the spiritual world. Spiritualism had begun with the infamous Fox sisters in the United States in 1848, then arrived in Britain in 1852, spreading quickly across the country. The spiritualists’ belief that the living could communicate with the dead dwelling in the spirit world was largely played out in the shape of the séance, in which participants would attempt to contact the spirits of dead family, friends and others through the conduit of a spirit medium. Participants in the activities of spiritualists ranged from amused dabblers to those who immersed themselves in systematic inquiry into and experiment of its method and purpose. As such, spiritualism appealed to all social classes. Queen Victoria was known to be interested and had sought to contact her husband Albert after his premature death in 1861.

Sceptics were numerous and vociferous, no more so than those in the medical profession. A typical stance could be found in the British Medical Journal, which during Houghton’s exhibition published an anti-spiritualist piece, in which the writer stated that ‘so-called spiritualistic manifestations are simply due to a particular nervous temperament, and to certain forms of disease that have long been recognised and are thoroughly understood by the medical profession’. Despite all this, Houghton brushed off these ‘scoffs of the ignorant’. Her Christian faith sustained her belief, not just in herself, but in her art.

Looking at Houghton’s otherworldly works now, they seem as fresh as the day they were made. Yet the question is not so much whether she was a pioneer of abstraction, but how she discovered this strange and beautiful language that was so out of step with what anyone else was doing at the time. Houghton was an artist revolutionary, battling alone amid a clamour of dissenters and satirists, and she never wavered from her purpose.

After her death, however, most of her work disappeared, with the majority of the remaining works finding their way to the Victorian Spiritualists’ Union in Melbourne, where they have been quietly cherished and cared for for decades. It has taken more than 140 years to bring her back into the light.

source: Georgiana Houghton, Houghton Tree, The Guardian, Cabinet of Curiosity, Tate Museum, Victoriana Web, Spectator, Hyperallergic, The Guardian, The Times, Studio International, Skeptical Occultist

Thanks! We enjoyed viewing this for our class on the occult. Cheers, RS 32, Stanford U, Fall 2017