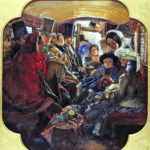

The Last of England by Ford Maddox Brown, 1855

It’s a desolate scene: a man, woman and tiny child, swaddled against the cold, stare forlornly from the back of a boat. The white cliffs of Dover slide over the horizon and they say good-bye to the last of England.

Painted by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Ford Maddox Brown in 1855 , The last of England was inspired by the emigration of one of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, sculptor Thomas Woolner. Discouraged by his lack of sales, Woolner, like so many other emigrants, was driven to try his luck on the Australian gold fields. He struck pay dirt down under, but it wasn’t gold he found, it was patronage.

Landing in Melbourne in 1852, Woolner bought kit and equipment and made his way around the traps from the diggings in the Ovens valley to the Fryer’s Creek, Castlemaine and Sandhurst areas. Like many other new chums, he soon realised he was not going to make his fortune fossicking for gold but in servicing the newly prosperous community in Victoria. He returned to Melbourne, sold his tools and set up as portraitist. Woolner had to dig and pug his own clay, which he used to model first friends, then, as word spread, fee-paying Melbourne dignitaries. He charged twenty-five guineas for a low relief portrait medallion cast in bronze, though he also made casts in plaster and terracotta.

Woolner had already made a small number of these medallions the year before he left London, notably of writers Thomas Carlyle, Alfred Tennyson and William Wordsworth which he hoped would find favour with the public, but these had attracted little attention.

In Australia he perfected the technique, making it his preferred format. The medallion was a relatively quick and economic means of portrait making, suitable to both old money and the nouveau arrivistes who were flattered to be portrayed in profile like illustrious Roman emperors, all noble brow and contoured silhouette. There was little competition beyond amateur whittlers, stonemasons and furniture carvers: it likely that Woolner was the first academy-trained sculptor to work in the colonies.

When he arrived in Melbourne, Woolner had stayed with Dr Godfrey Howitt, a doctor of medicine, and his wife Phoebe. Howitt’s passion for the flora and fauna of the Victorian region earned him a reputation as a botanist and entomologist. He owned land in the centre of the city and was associated with Melbourne Hospital. He was able to introduce Woolner to Melbourne society, bringing him in contact with Lieutenant Governor Charles Joseph La Trobe (1801-1875), administrator of the newly formed colony of Victoria and Woolner’s major patron during his time in Australia.

La Trobe had begun his colonial career in the West Indies in 1837. Within two years he was appointed superintendent of the Port Phillip District, then under the jurisdiction of the Governor of NSW, George Gipps. In 1850, Victoria became a colony and La Trobe was appointed its lieutenant-governor. He was not trained as an administrator and what skills he possessed were strained to the limit when gold was discovered a year later and the quiet backwater changed into an anarchic gold rush town virtually over night. It was an astonishing transformation: Melbourne had a population of 2,000 when La Trobe took up his post in 1839 and was the world’s richest city with 76,560 residents when he resigned in 1854. The son of a Moravian missionary, La Trobe was a social visionary who believed in the transformative power of education. In 1853 he set out, with Redmond Barry, to found a university and a free public library in the infant colony. He established the Botanic Gardens in 1854 and provided key support for other cultural projects such as the Mechanics’ Institute, the Melbourne Philharmonic Society and the Philosophical Society.

La Trobe’s patronage ensured that other commissions followed andWoolner made likenesses of Admiral Philip Parker King, Captain Cole, Governor-General Sir Charles Fitzroy, James Martin, William and James Macarthur and William Wentworth among others. Woolner repaid the debt to Dr Howitt with portraits of him and his wife, as well as Miss Edith Howitt and Charley Howitt, their children. In fact Woolner’s closeness to the family was such that he became engaged to Edith. However, the engagement broke down and Woolner left for England in July 1854, intending to return only if a promised commission for a full length statue of William Wentworth proceeded.

In all Woolner sculpted 24 portrait medallions during his two year stay in Australia, a sustained creative effort that has ensured his place in Australian history. But there is a postscript. In 1854 Woolner had met with Henry Parkes. The two maintained a correspondence and Parkes visited the artist in Britain in 1861 and 1882. Parkes assisted Woolner in securing the 1874 commission for the monumental bronze statue of James Cook that was erected in Hyde Park, Sydney as well as bids for other commissions of Sir James Martin and Sir Charles Cowper which never eventuated.

source: National Portrait Gallery