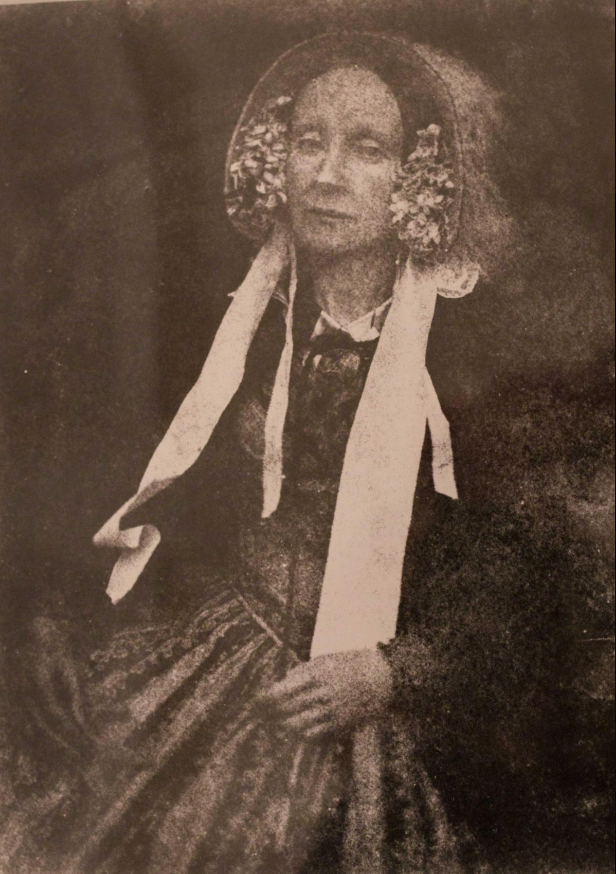

Jessie Mann, ca. 1844

Jesse Mann (20 January 1805 – 21 April 1867) was the studio assistant of the Scottish pioneering photographers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson. She is “a strong candidate as the first Scottish woman photographer” and one of the first women anywhere to be involved in photography.

Mann worked in the Hill & Adamson studio, Scotland’s first photographic studio in “Rock House”, on Calton Hill, Edinburgh for at least three years, until it closed after Adamson’s untimely death. She went on to become a school housekeeper.

It is reasoned that a print in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, of the King of Saxony in 1844, taken at the studio whilst Hill and Adamson were unavailable, was taken by Mann. The portrait was known to have been taken by an assistant to Hill and Adamson. Tate curator Carol Jacobi says this demonstrates that “she must have been part of their skilful understanding of how you set up a photograph, so she is a real pioneer.” A letter from the painter James Naysmith to Hill, written in 1845, praises Mann as “that most skillful and zealous of assistants“.

Mann was included in the 2016 exhibition at Tate Britain, Painting with Light: Art and Photography from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Modern Age.

She is one of the world’s photographic pioneers, a hitherto obscure Scottish woman who helped create some of the earliest photographic masterpieces.

Now a mysterious photographic portrait of a Scottish lady in a bonnet, sitting with blackened hand, has been identified as Jessie Mann, a Perthshire woman who lived in Edinburgh in the 1840s and was a key associate to the ground-breaking Scottish photographers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson.

The discovery comes as Ms Mann, and her crucial role in the development of early photography, is to be recognised officially for the first time in a major exhibition.

Roddy Simpson, a leading photohistorian and honorary research fellow at the University of Glasgow has identified the picture, a portrait of an Unknown Woman, as her.

The image, Unknown Woman 15 in the National Galleries of Scotland archives, shows the woman in a bonnet with a discoloured hand – Ms Mann is likely to have stained her hand using a chemical, silver nitrate, required at the time for the photographic process.

Silver nitrate blackens skin, and the calotype technique used by Hill, Adamson and Mann uses paper coated with silver.

The Tate’s show, curated by Carol Jacobi, curator of British Art, features an image of Two Women in Bonnets, taken in the 1840s. One of these women is now firmly identified as Jessie Mann, and was the basis for an image of her in a major painting of the Free Church’s Disruption of 1843, painted by Hill.

Ms Jacobi said: “This is a very good opportunity to bring her into better view – she was present right at the start of modern photography and was a clearly a key figure in their work.”

The Disruption painting, a large work painted by Hill over 20 years with its portraits based on photographs, is also in the show.

Mr Simpson, who has unearthed many of the scant details of her life, said of the new image: “The bonnet, the high brow, she really could be Jessie Mann – early photography was a dark art and her hands were likely stained by silver nitrate.”

He added: “It was general knowledge in Edinburgh at the time that she was working with Hill and Adamson on their photography. (…) There are no official images of her, but this could be her. Naysmith wrote about her, and what she contributed to their work is open to speculation. (…) She probably did a lot of printing and processing. She was obviously quite sophisticated and educated – she was definitely an associate, not a servant. (…) This exhibition is exciting because she is being acknowledged for the first time, one of the first women to be involved in photography, Hill and Adamson revolutionised it and she was a key contributor.”

Hill and Adamson created thousands of calotype portraits, views and landscapes, and have been acknowledged as the forefathers of modern photography. More than 5000 of their images are held by the National Galleries of Scotland.

Hill, a painter and member of the artistic establishment, teamed up with Adamson, a master of early photographic techniques. They hired Miss Mann to help them capture the likenesses of the 450 ministers who had seceded from the Church of Scotland in the Great Disruption to form the Free Church of Scotland.

Two other British women involved in photography in the 1840s were Anna Atkins and Constance Talbot.

source: The Herald Scotland